3.0 Description of the County

3.1 Demographics, location, topography, and climatic data

Storey County, located in western Nevada, is the second smallest county in Nevada at approximately 167,620 acres in size. Only about nine percent of Storey County is administered by the federal government, the smallest percentage of any Nevada County. The Bureau of Indian Affairs administers a trace amount and the remainder (about 91 percent) is private land. A summary of land status acreages is provided in Table 3-1.

| Land Administrator | Approximate Acreage | |

|---|---|---|

| BLM | 14,980 | |

| Private | 152,200 | |

| BIA | 440 | |

| Source: BLM land ownership GIS database. | ||

The discovery of gold at the head of Gold Canyon in 1859 prompted an influx of people to this area, a development that led to statehood for Nevada five years later. Today the county holds a population estimated at around 3,700 people. Of those, about 1,200 people live in the towns of Virginia City and Gold Hill (Nevada State Demographer’s Office, 2003). The other two thirds of the population resides in the communities of Lockwood, Virginia Highlands, and Six Mile. Mining has given way to tourism as the leading element of the County’s economy. Virginia City has been the County Seat since territorial times.

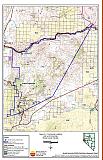

Elevations within the county range from 7,836 feet in the Virginia Range to 4,057 feet in Long Valley. Primary mountain ranges include the Virginia Range and the Flowery Range. The major valley in the county is Long Valley, which drains the western part of the county and flows into the Truckee River at Lockwood. General information for Storey County is shown in Figure 3-1.

The Truckee River separates Storey County from Washoe County to the north. State Routes 341 and 342 are the primary transportation corridors. US Highway 50 and the Carson River to the south lie just beyond the county line in Lyon County.

3.2 Wildfire History

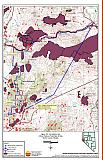

Few wildfire ignitions have been recorded for Storey County over the last 24 years. However some large wildfires have occurred. The Gooseberry Mine II fire in 1985 started in Storey County and burned over 20,000 acres as it crossed into Lyon County (Reinhardt, pers. comm.). Fires that occur on private lands are predominantly recorded on paper maps and are often not included in the GIS datasets. Wherever possible, anecdotal information from fire professionals and local residents was added to the database information. Available fire datasets suggest that 34 percent of the county has burned during the last 24 years. Table 3-2 summarizes the fire histories and fire ignitions that have been recorded in the database since 1980. Figure 3-2 illustrates the fire history on a map of Storey County.

| Year | Number of Fire Ignitions | Total Fire Acreage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 1981 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 1982 | 2 | 370* | |||

| 1983 | 1 | 3,285 | |||

| 1984 | 1 | NA | |||

| 1985 | 1 | 27,194* | |||

| 1986 | 1 | NA | |||

| 1987 | 3 | 265* | |||

| 1988 | 1 | NA | |||

| 1989 | 4 | 15 | |||

| 1990 | 1 | 342* | |||

| 1991 | 3 | NA | |||

| 1992 | 2 | 0 | |||

| 1993 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 1994 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 1995 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 1996 | 2 | 472* | |||

| 1997 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 1998 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 1999 | 2 | 17,880 | |||

| 2000 | 0 | 7,620 | |||

| 2001 | 5 | 64 | |||

| 2002 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 2003 | 3 | 97 | |||

| TOTAL | 38 | 57,604 | |||

| NA = Information Not Available | |||||

| Source: Fire history data provided by the National Interagency Fire Center, Boise, Idaho, BLM Nevada State Office, and USFS Humboldt-Toiyabe Supervisor’s Office. Additional fire history information provided by Jim Reinhardt, personal communication. | |||||

3.2.1 Ignition Risk Factors

Wildfire ignition risks fall into two categories: lightning and human caused. Human caused ignitions can come from a variety of sources such as burning material thrown out of vehicle windows or ignited during auto accidents, off-road vehicles, railroads, arcing power lines, agricultural fires, campfires, debris burning in piles or burn barrels, matches, and fireworks. In Storey County, database records indicate that eight of the 38 wildland fire incidents recorded were due to lightning. Of the remaining thirty fires, ten were human caused and twenty had unreported causes of ignition.

3.2.2 Fire Ecology

The science of fire ecology is the study of how fire contributes to plant community structure and species composition. A ’fire regime’ is defined in terms of the average number of years between fires under natural conditions (fire frequency), and the amount of dominant vegetation replacement (fire severity). Natural fire regimes have been affected throughout most of Nevada by twentieth century fire suppression policies. Large areas that formerly burned with high frequency but low intensity (fires more amenable to control and suppression) are now characterized by large accumulations of unburned fuels, which once ignited, will burn at higher intensities.

Big sagebrush is the most common plant community in Nevada with an altered fire regime, now characterized by infrequent, high-intensity fires. Sagebrush requires ten to twenty or more years to reestablish on burned areas. During the interim these areas can provide the conditions for establishment and spread of invasive species and in some cases inhibit sagebrush reestablishment. The most common invasive species to reoccupy burned areas in northern Nevada is cheatgrass.

Effect of Cheatgrass on Fire Ecology

Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) is a common introduced annual grass that aggressively invades disturbed areas, especially burns. Replacement of a native shrub community with a pure stand of cheatgrass increases the susceptibility of an area to repeated wildfire ignitions, especially in late summer when desiccating winds and lightning activity are more prevalent. The annual production or volume of cheatgrass fuel produced each year is highly variable and dependent on winter and spring precipitation. Plants can be sparse and range from only a few inches tall in a dry year to over two feet tall on the same site in wet years. In a normal or above normal precipitation year, cheatgrass can be considered a high hazard fuel type. In dry years cheatgrass poses a low fire behavior hazard because it tends to burn with a relatively low intensity. Nevertheless, every year dried cheatgrass creates a highly flammable fuel bed that is easily ignited and has the propensity to rapidly burn and spread fire into adjacent cover types, which may be characterized by more severe and hazardous fire behavior. The ecologic risk of a fire spreading from a cheatgrass stand into adjacent, unburned native vegetation is that additional undisturbed areas are thereby opened by the fire disturbance and are vulnerable to cheatgrass invasion. Associated losses of natural resource values such as wildlife habitat, soil stability, and watershed functions are additional risks.

Eliminating cheatgrass is an arduous task. Mowing defensible space and fuelbreak areas annually before seed maturity is effective in reducing cheatgrass growth. In areas where livestock may be utilized, implementing early-season intensive grazing up to and during flowering may aid in depleting the seed bank and reduce the annual fuel load (BLM 2003, Davison and Smith 2000, Montana State University (2004)[1]. It may take years of intensive treatment efforts to control cheatgrass in a given area but it is a desirable conservation objective in order to revert the landscape to the natural fire cycle and reduce the occurrence of large, catastrophic wildfires. Community-wide efforts in cooperation with county, state, and federal agencies are necessary for successful cheatgrass reduction treatments.

Fire Ecology in Pinyon-Juniper Woodlands

Singleleaf pinyon (Pinus monophylla) and Utah juniper (Juniperus osteosperma) are the dominant components of a plant community commonly referred to as Pinyon-Juniper (P-J). P-J woodlands were primarily confined to the steeper slopes commonly found at higher elevations in the Great Basin prior to European settlement. These woodland communities were characterized by a discontinuous distribution on the landscape and a heterogeneous internal fuel structure: a mosaic pattern of shrubs and trees resulting from the canopy openings created by small and frequent wildfires.

Both pinyon and juniper trees have relatively thin bark with continuous branching all the way to the ground. In dense stands, lower tree branches frequently intercept adjacent ladder fuels, e.g. shrubs, herbaceous groundcover, and smaller trees. This situation creates a dangerous fuel condition where ground fires can be carried into tree canopies, which often results in crown fires. A crown fire is the most perilous of all wildfire conditions and is usually catastrophic in nature since the danger to firefighters is generally too great to deploy ground crews.

Over the last 100 years, wildfires in most of the western United States have been aggressively suppressed and P-J woodlands have encroached over areas traditionally occupied by other plant communities. Tree canopy coverage has been greatly expanded and has reached as high as sixty percent or more in some areas, contributing to the loss of diverse shrublands. These dense woodlands are perceived as desirable for urban expansion in contrast to the surrounding deserts. In areas where human occupation in P-J woodlands has grown over the last fifty years, the option of returning to a natural fire regime becomes increasingly problematic.

3.3 Natural Resources and Critical Features Potentially at Risk

Critical features at risk of loss during a wildfire event can be economic assets such as agricultural and industrial resources or cultural features such as historic structures, archaeological sites, and recreation-based resources.

3.3.1 Historical Registers

There are twelve sites listed on the National Register of Historical Places for Storey County. The Nevada State Register of Historical Places lists one site. The effects of fire on cultural and historical resources depend upon factors that vary on a site-specific basis such as fuels, terrain, site type, and cultural or historical materials present. Archeological sites such as the Largomarsino Petroglyph site, rock art, ceramics, and rock artifacts can be damaged or destroyed by extremely hot fires.

Tourism is a significant economic base for Storey County. Virginia City is a primary tourist attraction in northwestern Nevada. The tourism industry in Virginia City and Gold Hill is centered around the historic features and mining heritage of that area. The Virginia City Historic District is registered as a National Historic Landmark and includes seven buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Many of these Comstock era buildings and cotemporaneous neighbors lie in the wildland-urban interface and are at risk of permanent loss and destruction in the event of a wildfire in the Virginia City area. The Silver Terrace Cemeteries (also known as the Virginia City Cemeteries) to the north of town contain historical artifacts from the 19th and 20th centuries that would be better protected from the threat of wildfire with implementation of mitigation treatments.

3.3.2 Flora and Fauna

Eleven species from the Sensitive Taxa list are protected by Nevada state legislation and are identified in Table 3-3 (Nevada Natural Heritage Program database; last updated for Storey County 18 March 2004). The Nevada Natural Heritage Program, the Nevada Division of Forestry, and the Nevada Department of Wildlife should be consulted regarding specific concerns and potential mitigation to minimize impacts to these species and their habitat prior to the event of a catastrophic wildfire or in the implementation of projects intended to reduce the threat of wildfires to a community.

| Common name | Scientific name | Legislation |

|---|---|---|

| Plants | ||

| Sand cholla | Opuntia pulchella | NRS 527.260.120 |

| Mammals | ||

| Spotted bat | Euderma maculatum | NRS 501 |

| River otter | Lontra canadensis | NRS 501 |

| Birds | ||

| Northern goshawk | Accipiter gentilis | NRS 501 |

| Western burrowing owl | Athene cunicularia hypugaea | NRS 501 |

| Ferruginous hawk | Buteo regalis | NRS 501 |

| Swainson’s hawk | Buteo swainsoni | NRS 501 |

| Greater sage-grouse | Centrocercus urophasianus | NRS 501 |

| Black tern | Choldonias niger | NRS 501 |

| Flammulated owl | Otus flammeolus | NRS 501 |

| White-faced ibis | Plegadis chichi | NRS 501 |

Fishing is an important recreational resource for the area. The Truckee River traverses roughly 25 miles of the Storey County line. The Truckee River is home to two federally listed fish: the Lahontan Cutthroat Trout (federally listed as threatened) and the Cui-ui (federally listed as endangered). The ability of the Truckee River watershed to receive, store, and transmit water is related to the geology, vegetation, and soil within the associated watersheds. While Storey County contributes to only a small portion of the Truckee River watershed, excessive erosion from burned areas within the associated watersheds could significantly increase sedimentation of spawning beds and impact water quality for fisheries in the lower Truckee River.

3.4 Previous Fire Hazard Reduction Projects

In March 2002, the Fire Safe Highlands Coalition became the first self-directed citizens group to become a formally affiliated chapter of the Nevada Fire Safe Council. This group has been influential in spearheading fire safety activities in collaboration with the Storey County Fire Department and the Nevada Division of Forestry. In June of 2002, the coalition, in collaboration with the University of Nevada, Reno - Cooperative Extension, contracted with Resource Concepts, Inc. to produce the Community Wildfire Risk Assessment and Fuel Reduction Plan for the Virginia Highlands Community. The parties involved include the Storey County Fire Department, Storey County Emergency Management Department, Local Emergency Planning Committee, the Virginia Highlands Volunteer Fire Department, and the Fire Safe Highlands Coalition. Recommendations from the plan and previous projects initiated by the Storey County Fire Department have led to the installation of a warning siren, the development and distribution of a fire evacuation plan, and improved marking of residential addresses and escape routes. Fire suppression capacity has been improved through the installation of eleven additional underground storage tanks, increasing fire-grade water storage capacity by 240,000 gallons. Approximately one hundred houses have benefited from defensible space activities through a grant from the Nevada Fire Safe Council. The Nevada Division of Forestry is completing fire hazard assessments on individual private parcels and promoting defensible space implementation. The SCA Fire Education Corps evaluated individual homes in Virginia Highlands in 2003.

Grant money obtained through the assistance of the Nevada Fire Safe Council has been used by the local Highlands Chapter of the Fire Safe Council to complete substantial portions of the fire hazard reduction projects in the community. Limited grant funding for the implementation of fuels reduction treatments was allocated by a lottery and defensible space activities were limited to individual homeowner initiative and seasonal NDF crews who were clearing dead trees from the area. The chapter is expecting to administer a new grant disbursement in fall 2004 and spring 2005, with plans to implement a fuelbreak along Cartwright Road. Fuelbreaks are also proposed along Yellowjacket Road and Highway 341, which are well situated to protect the western flank of the community with fuel reduction enhancements (J. Copeland, pers. comm.).

In addition to individual homeowners implementing defensible space treatments around their residences, other fuels reduction projects have removed over 700 tons of combustible material from the Virginia Highlands area (P. Murphy, pers. comm). Projects have included the preparation of a demonstration parcel on Lousetown Road and a dead tree hunt, where community members identified over 400 dead or dying trees for removal from sixteen parcels on Geiger Grade.

The coalition has also purchased a trailer that is available to Virginia Highland residents to facilitate the timely removal of cleared brush to a designated burn pile next to the fire station. Public education events such as workshops on defensible space sponsored by the BLM Carson City Field Office, as well as pine beetle activity, evacuation protocol, and a demonstration by NDF of fireproofing gel for homeowners, have contributed to an improved understanding of the interaction between this landscape and its residents.

The Chapter’s web page (www.firesafehighlands.org) is an example of active engagement in fire safe education by and for homeowners.

Figure 3-1Community Locations and Land Ownership, Storey County, Nevada |

|

Figure 3-2Fire History and Critical Features Potentially At Risk, Storey County, Nevada |

|